(An illustrated paper presented at the Fast Forward: Women in Photography Conference, Tate Modern, London, 6-7 November 2015)

The full presentation can be viewed as a video here: Tate / Fast Forward

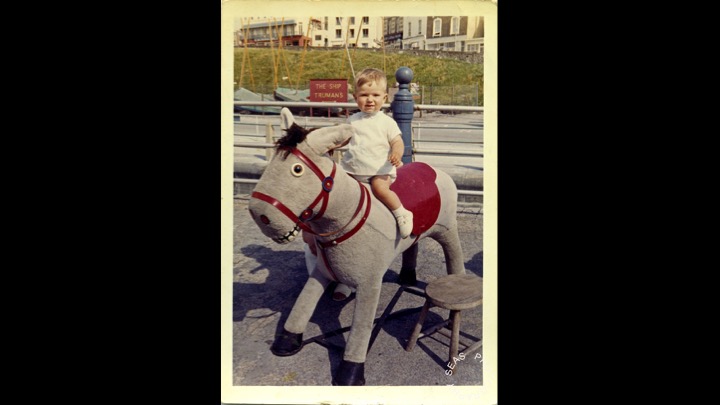

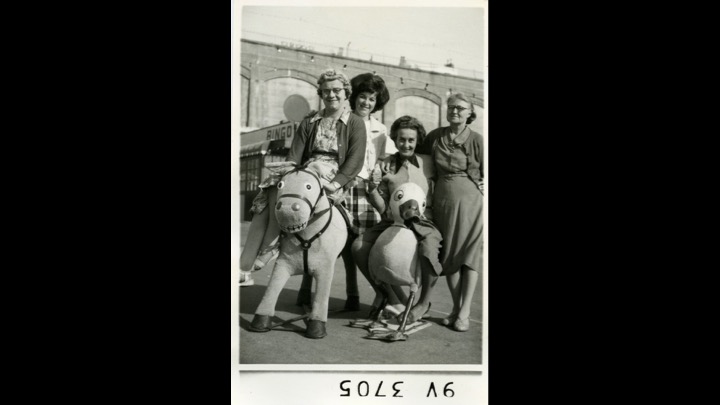

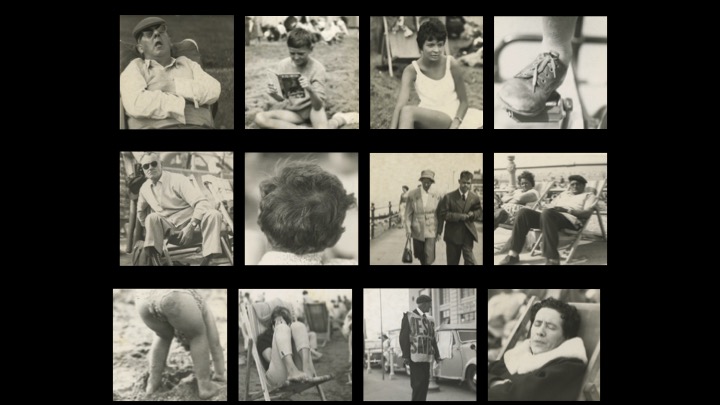

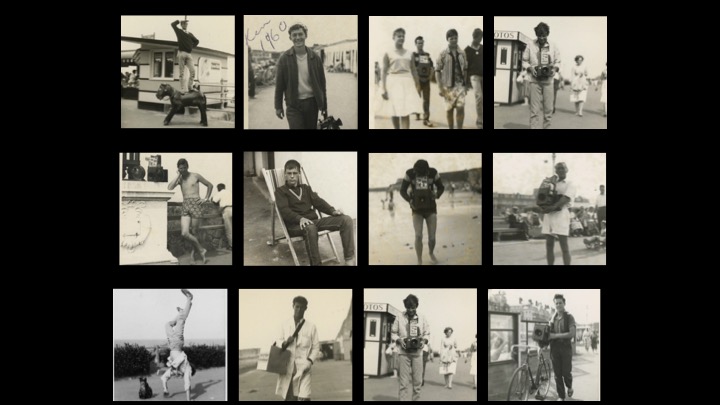

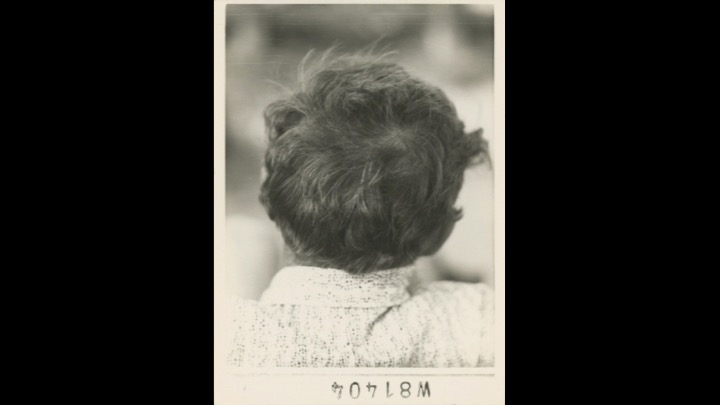

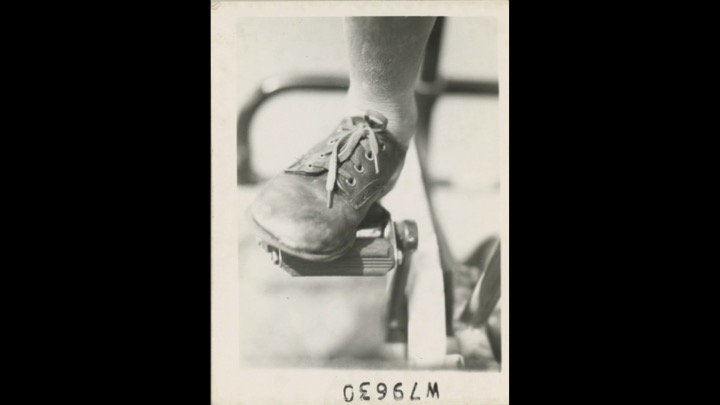

This illustrated paper provided insight into the practice of commercial seaside photography, offering a visual exposition of the British seaside as represented through the refracted lens of the female beach photographer. The research upon which this paper was based provides new insights into an overlooked form of demotic photography and the role women played in this commercial practice, thereby opening up rich seams of imagery and revealing new perspectives on photographic working methods.

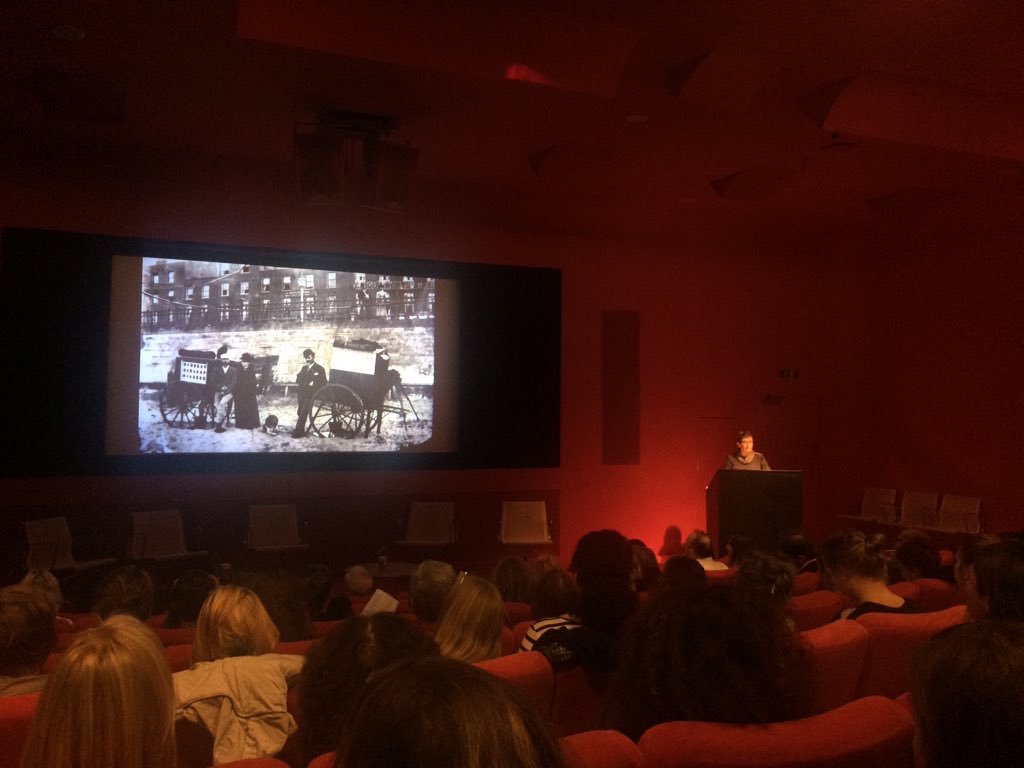

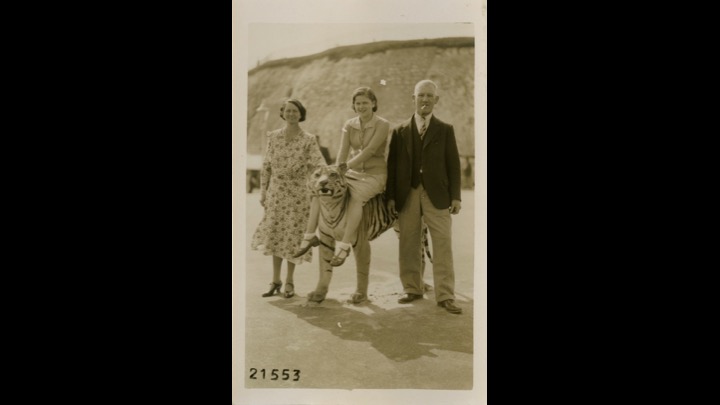

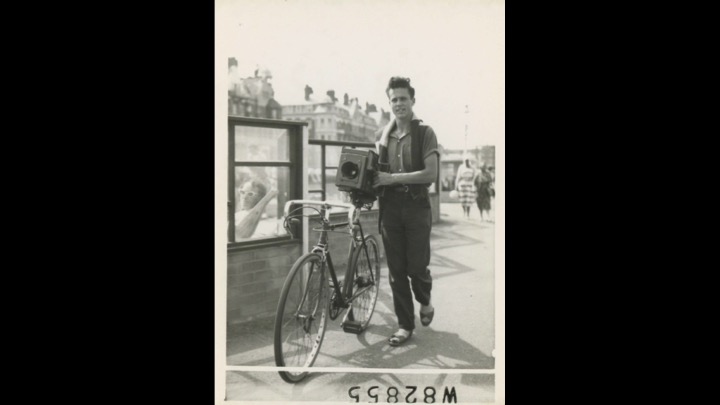

This paper examined commercial seaside photographic practice, offering an exposition of the British seaside photographer as she evolved from the itinerant individual to resident employee within an organised structure. The role of seaside photographer had in its early history been couched in derogatory terms such as ‘Smudger’ or ‘Bodger’ and generally and regardless of gender regarded as an inept and relentless seaside pest. Seaside photography companies such as Sunbeam on the Isle of Thanet and Barkers of Great Yarmouth provide examples of large commercial photographic companies located at the coast, which from the 1920s strategically sought to counter the negative connotations surrounding the seaside photographer. One way in which they sought to revise public perception was through the employment of articulate, attractive and proficient women photographers – projecting an overt professionalism cloaked in femininity and informality.

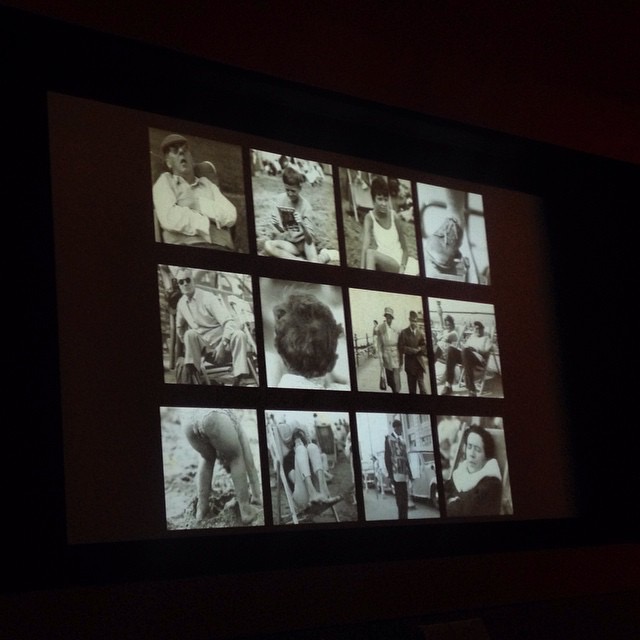

The history, politics and aesthetics of commercial seaside photography remains a largely overlooked form of commercial practice and amplified still further is the lack of examination of women’s location in this practice. Within commercial seaside companies, women were always present, but predominantly marginalised to backroom tasks of quality control, retouching, administration or, in the public sphere, as kiosk attendants. However, a number of women did become seasonal seaside photographers. Case studies, interviews and visual research show how their practice differed from highly standardised means of production and how this differentiation was harnessed by the women in order to achieve commercial success and recognition on their terms. This was despite the motivation for their initial employment arguably being rooted in the employer superficially considering how attractive young women could function as a hook for holidaying clients to purchase cheap commercially taken seaside portraits. Not only were these young women photographers producing photography that equalled their male counterparts in both method and aesthetic the women’s photography as this research reveals, differentiated itself and provided an alternative visual voice.

The paper’s subject, whilst seemingly esoteric and even prosaic, nevertheless importantly illustrates how women have harnessed photography and photographic practices as a mode of not only expression but also as means of physical liberation and economic self-sufficiency.