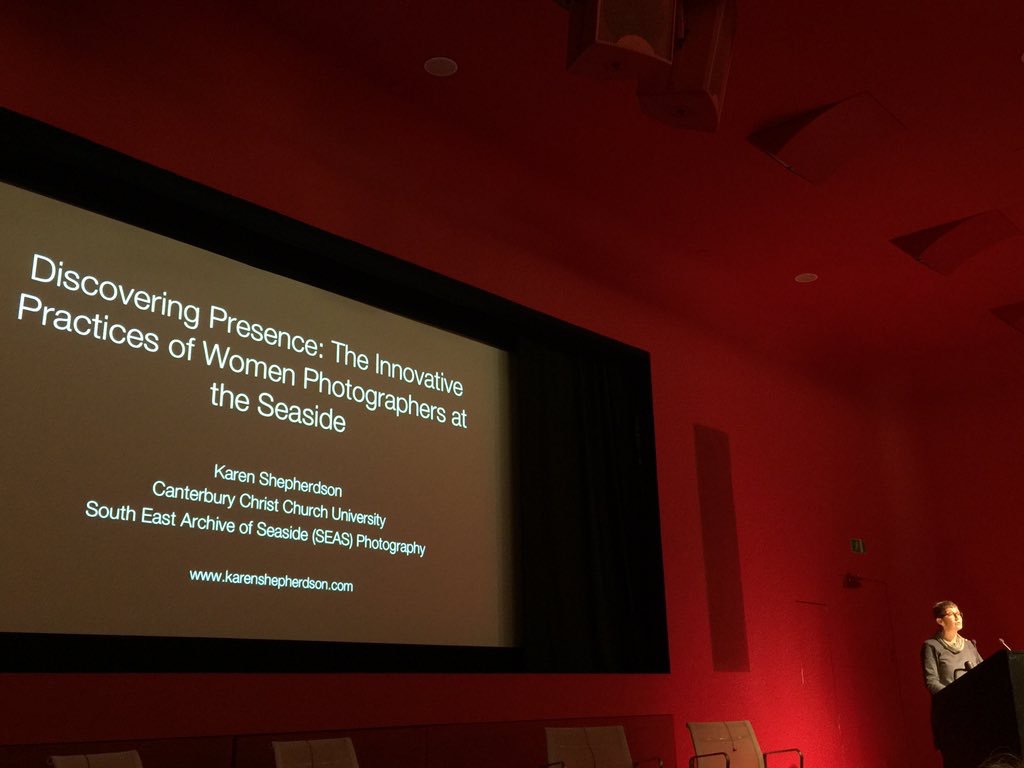

WESTMINSTER SYMPOSIUM 2017

Researching, Writing and Exhibiting Photography: a Symposium

‘Photography at the Edge’

SLIDE

Given the panel I am on, I do feel the requirement to foreground my diverse working life as a: photographer, curator, director of an archive, co-director of a centre for research on communities and cultures, co-editor for the Journal for Photography & Culture… and ah!, yes! as a writer too!

For me, certainly since 2010 (I came to photography rather late in life) the interchange between writing and practice (and by practice I refer back to particularly the making of photographs and the curation of both photographic festivals and exhibitions) is seamless. These activities are not discrete from one another, but inform each other and for me personally distill experience rather than dilute.

But, rather like the elephant we see in Larson’s cartoon,

SLIDE

when asked to speak on one of the subjects – in this case writing - I feel uncertain and somewhat exposed – I fear what might be expected is mastery in one, when I can provide at best proficiency in some. Unlike the elephant I play neither piano nor flute, but to extend the orchesteral analogy perhaps to breaking point – I think of my working life as being akin to a percussionist, working across instruments which whilst perhaps appearing highly diverse, do indeed share a strong family relationship.

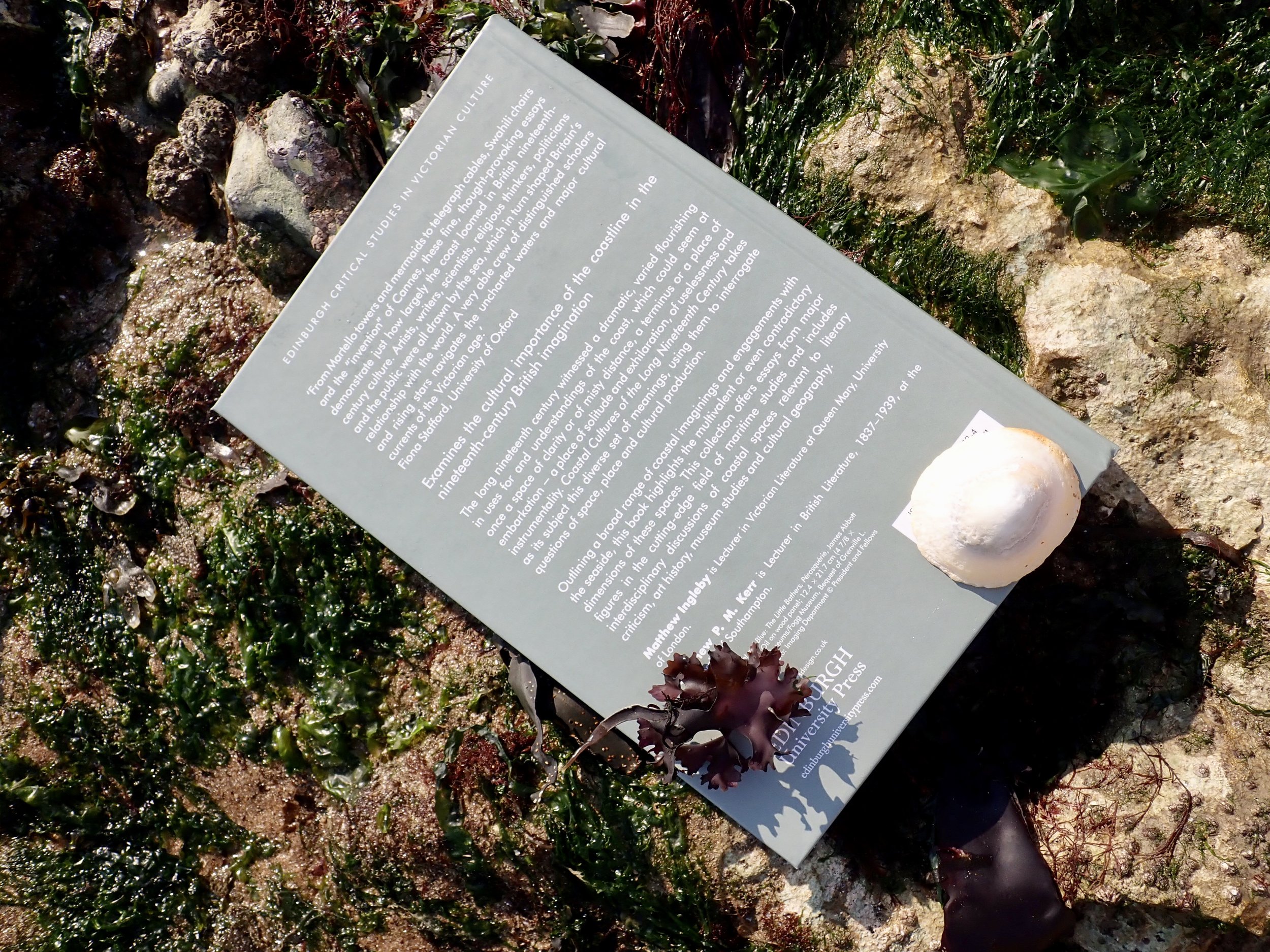

My life is lived as a coastliner – at the very south east margin of the UK, closer to Europe (at least now geographically) than to any city – certainly London. I live and work as Fay Godwin’s 1995 book is titled at The Edge of the Land.

My home is on the Isle of Thanet which is perhaps best known for its coastal towns of Ramsgate, Broadstairs and Margate which make up the Isle of Thanet. I am within and part of that complex coastal community which very recently has found itself in the bewildering position of being back in fashion – in reality Thanet is a place which has endured decades of decline and disregard.

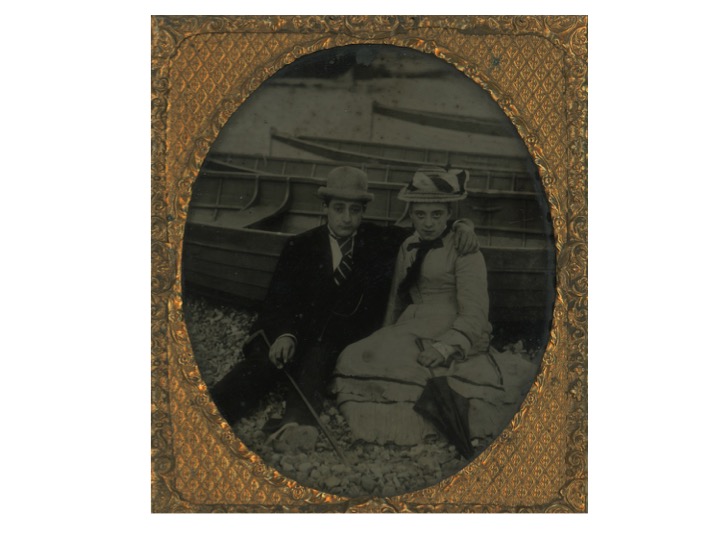

SLIDE X3

Living and working at the edge made me want to find ways of telling the stories of coastal communities such as mine – and in the telling contribute to a recalibration of perception of this place and space.

How might I use everything in my intellectual and creative armoury to at least have coastal communities such as mine acknowledged.

Today I will talk about how as a maker of photography – and a maker in the broadest sense - as a writer, photograher, curator etc, - a hybrid - a mongrel, I mediate and in doing so I re-member and re-shape an actuality.

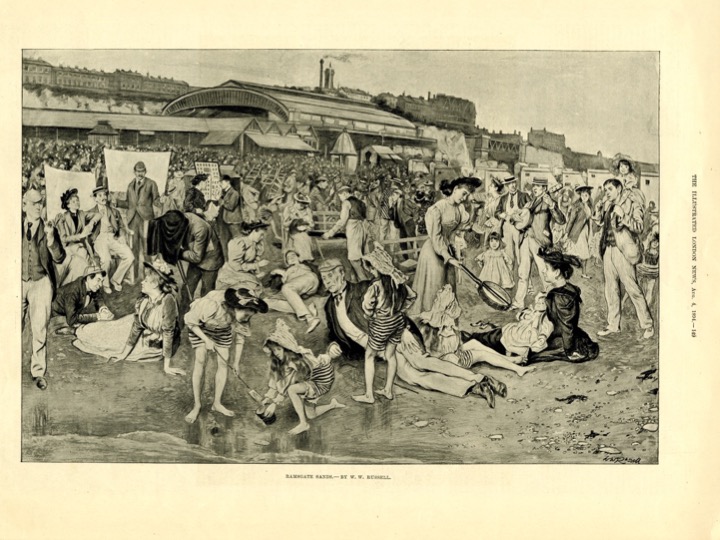

In doing this I’m going to draw upon a range of seaside imagery and writing.

SLIDE

For me, photography-as-writing provides a potent conduit for harvesting and then telling stories about other things – things that matter to me and by mediating re-membered experiences through the medium of photography and photography-as-writing I aim to make coastal lives connect with others – usually using the photograph as object, cloaked in words, generating a connective tissue between a re-membered, usually a demotic experience - and its re-telling to others.

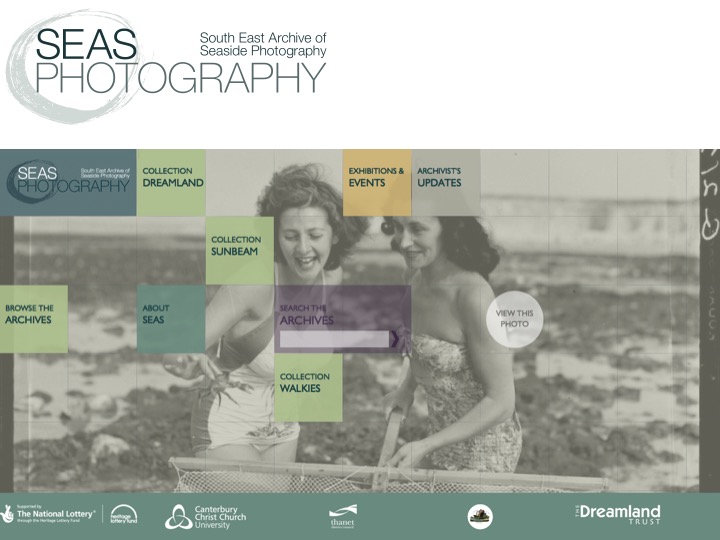

One of my roles is as Director of a photographic archive – its called the South East Archive of Seaside Photography – commonly known as SEAS Photography which specialises – unsurprisingly given its name – on archiving commercially made seaside images, taken along the UK’s south eastern coastline from around 1850 onwards. As an Archive we exhibit locally, regionally, nationally and from next year internationally, and produce supporting materials in the form of articles, monographs, exhibition catalogues etc. In addition, we have a large and very accessible, overtly unacademic / public-friendly website…

SLIDE

and seek to engage with the public through coastal community gatherings and events - it is these gatherings which has led to the findings explored in the first 2/3s of this presentation.

As I hope we shall see, commercial seaside photography – which could so readily be defined as prosaic and ephemeral - has not only endured, but reveals an unexpected, unintended, emotional potency.

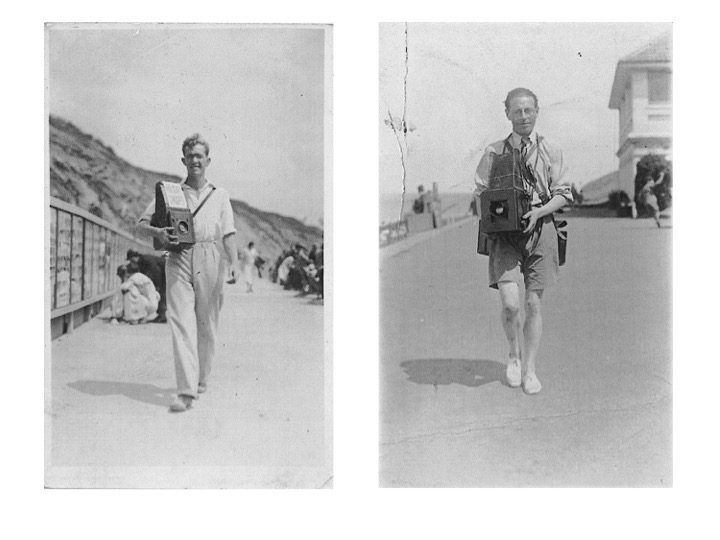

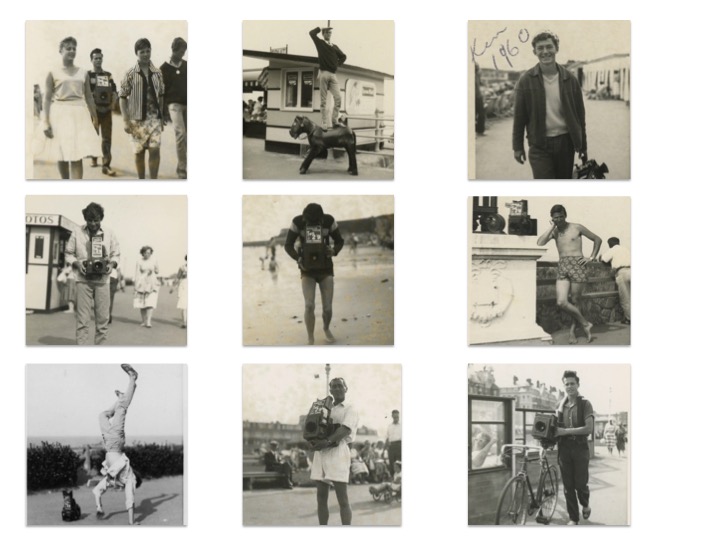

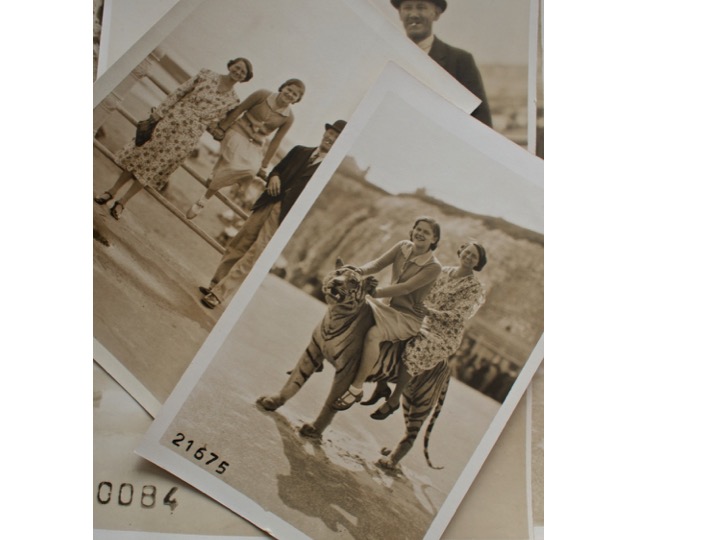

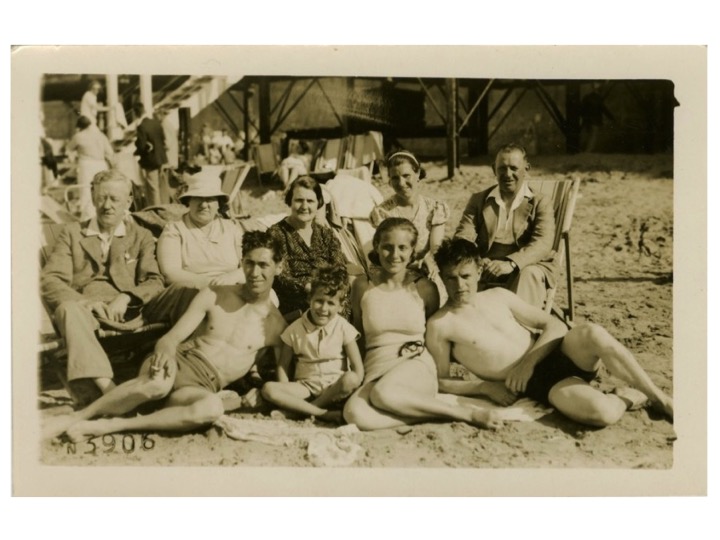

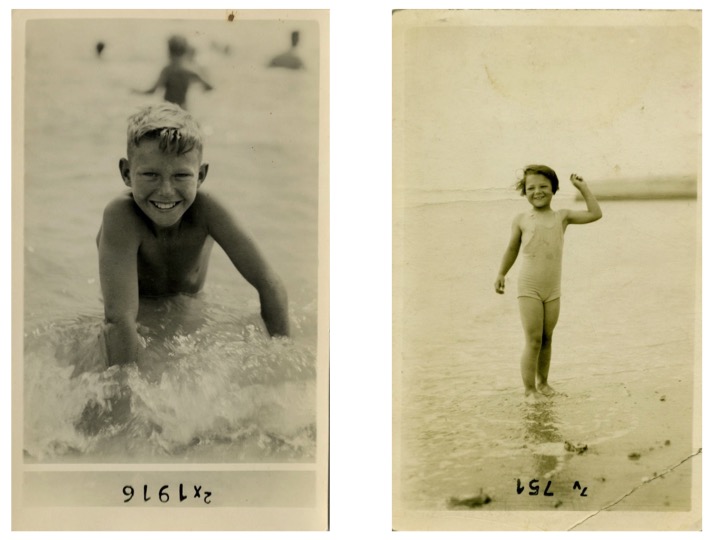

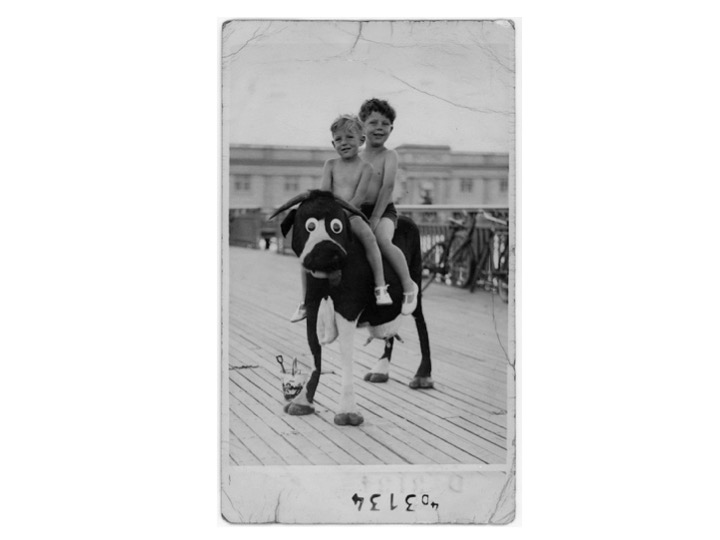

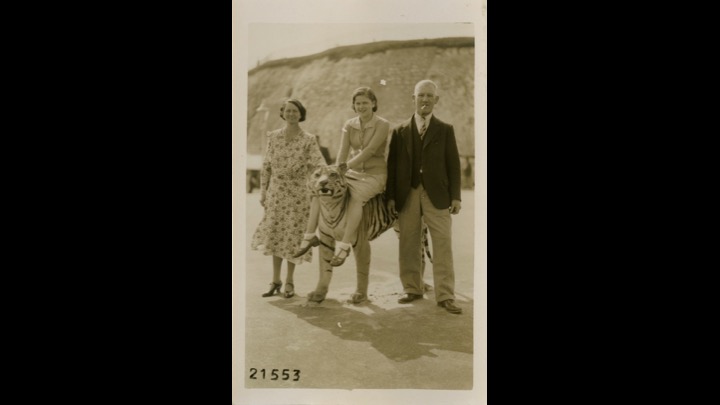

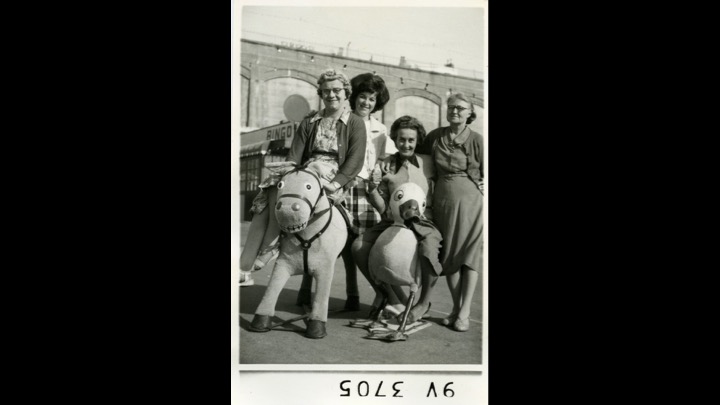

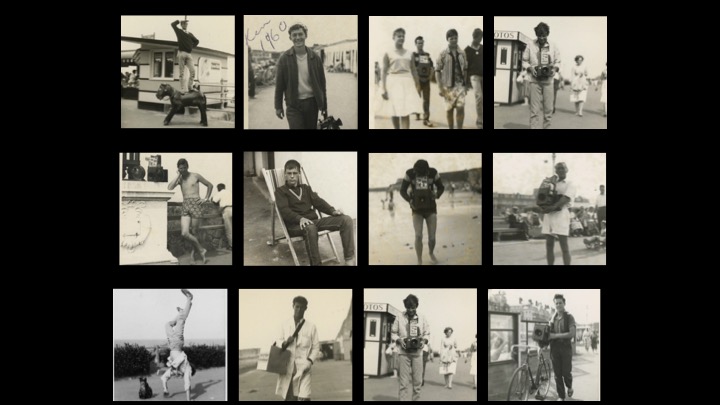

SLIDE X3

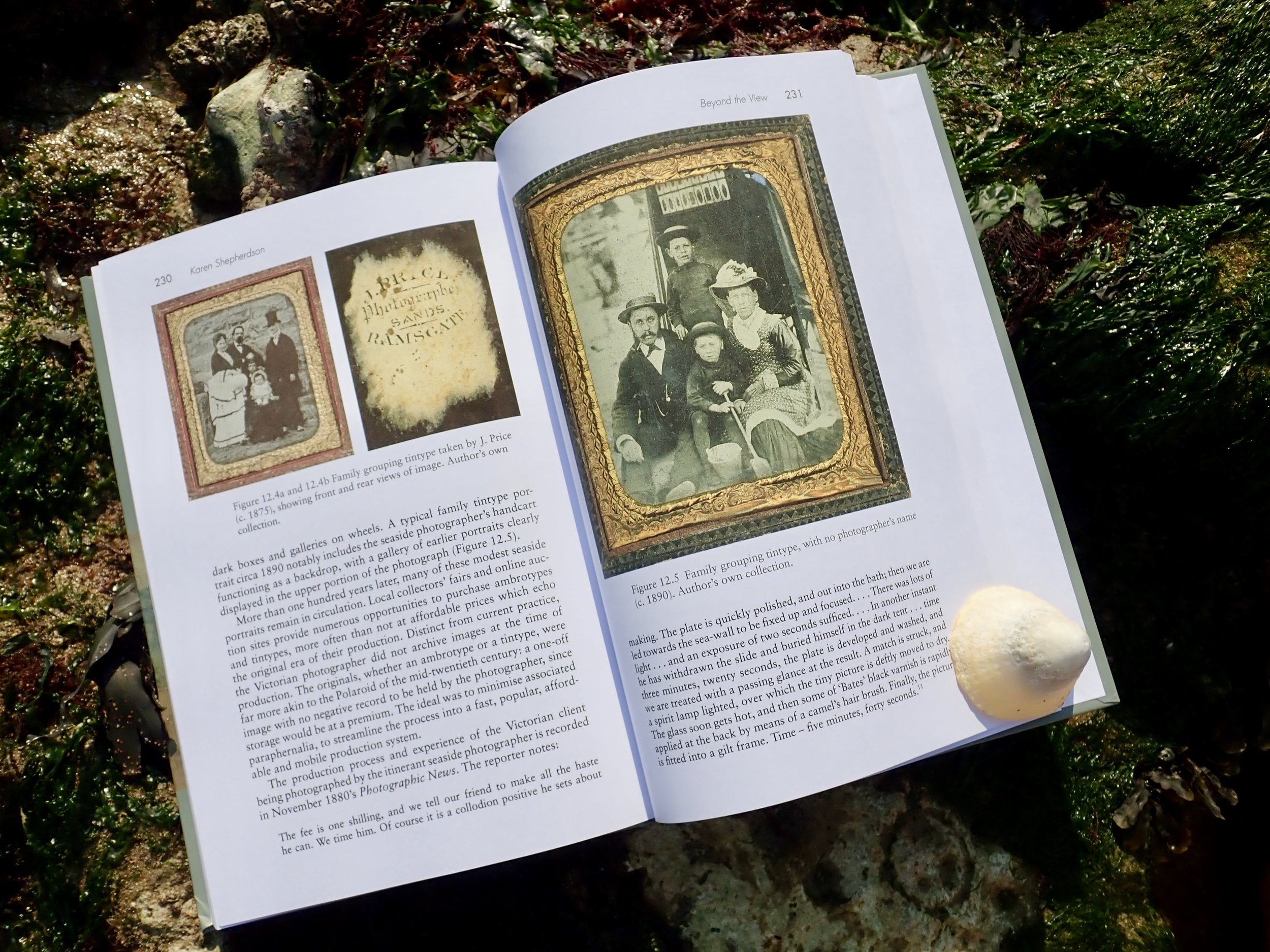

Just a little context with regards to Commercial seaside photography:

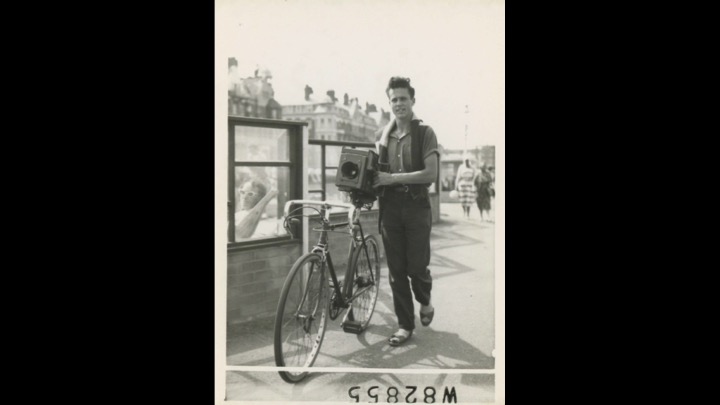

This type of production was present from the mid C19, but it is these mid C20 photograhs where my initial focus today resides, by this time commercial seaside photography was a highly systematised process, based upon the division of labour and a capitalist model of, crudely speaking: stack ‘em high / sell ‘em cheap.

This was characterized by young, often very attractive – normally male - summer-season photographers - as we see here X2 - being employed to photograph people enjoying the promenade and beach.

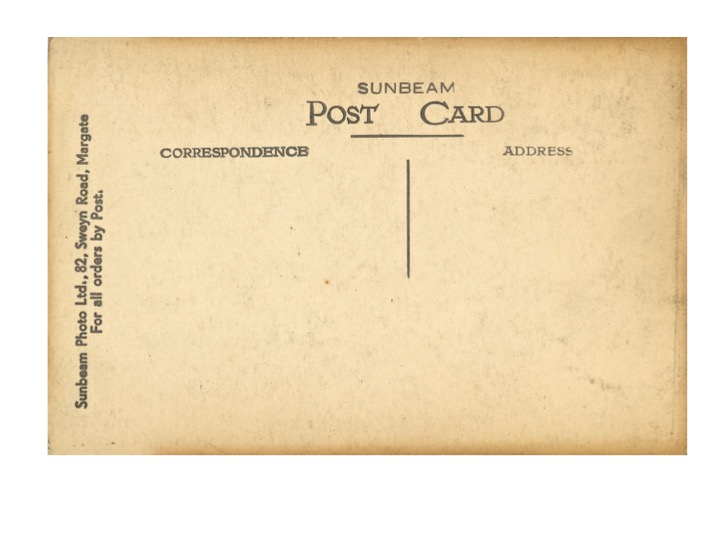

Yet despite mass production and the connotation of such photography as little more than disposable seaside wares - these images,

SLIDE

predominantly in the form of picture postcards as we see here – have indeed endured. We know that hundreds of thousands X6, if not millions of these photographs were taken and yet most of these images are now found only within domestic family albums…

If photographs were not sold and thus kept by the buyer at the time of taking, they would routinely be discarded or pulped by the photographer/photographic company, with no archive or record kept. We at the Archive – at SEAS Photography - have sought to counter this lack of record and in an attempt to uncover, document, exhibit and write about these privately held pictures, we have organised numerous Community Collection Days.

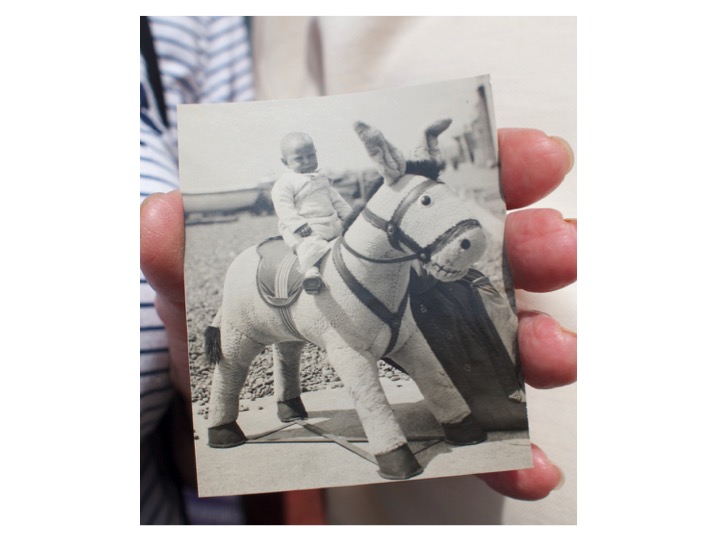

SLIDE

Here members of the public can see examples from the Archive, bring along their own commercially taken seaside photographs which are scanned and at this point we attribute names and importantly any additional narrative information such as dates and whereabouts.

It is very seldom - I can count on the fingers of perhaps one hand - how many times a donor has allowed us to actually keep the postcard photograph – rather than just take a digital copy. Indicative perhaps of the emotional – not monetary - value such material objects have for the individual families.

SLIDE

Five years ago and new to the role as Archive director, what I hadn’t envisaged was just how significant these humble objects were to their owners – which at the time of production would have cost just pennies to buy. I also had to quickly understand that each image-donor told the picture’s narrative, not as history – but as memory. Perhaps not an accurate memory – but nevertheless recounting the narrative as if an important memory.

Maurice Halbwach’s persuasive thesis is I think salient here, drawing as it does a distinction between that of history and that of memory. At the Archive we have become very aware that for the image-donors their contributions are not considered by them as ‘history’ – they’re neither a formal nor a written account mediated through an academic or official lens. These modest material objects are potent visual connective tissue linking the donor to their, or their families, (re)membered past.

The connective tissue between their reality of now and their (re)membered experience of then.

It is inevitably a selective and reconstructive process, where distortion of narrative, of editing of fact does take place, whereby (re)membering a past rather than ‘The Past’ and a truth rather than ‘The Truth’ is produced.

A past and truth made all the more binding through the act of telling at the community events. But of course in the harvesting of these tales I also risk hijacking them, as I place them into an academic context though writing or in presentations such as today.

I rapidly am able to understand in the academic sense what I am seeing and hearing at these community events. I’ve read my Barthes, my Sontag, my Batchen and it’s powerful to observe how the haptic qualities of these modest postcard photographs initiate certain repeated responses which are ‘touching’ - and ‘touching’ in the very many senses of that word:

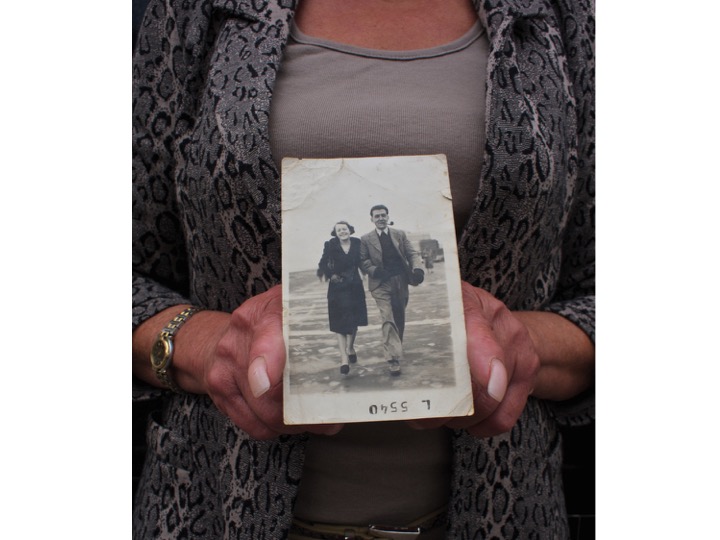

SLIDE

I see the physical touching: the tender holding, presenting and stroking of the image;

SLIDE

I see the donor emotionally touched when re-membering the image’s context

SLIDE

and I too am touched too by the stories I hear – it is touching to witness.

To provoke this further, I will share three pieces of writing – where like a porter at the railway station shifting luggage, I move – perhaps very clumsily – the experiences of others and myself into the public domain, through image and text:

Writing #1

As I have said I am touched by the stories I hear – it is touching to witness and one memorable, but certainly not untypical example is…

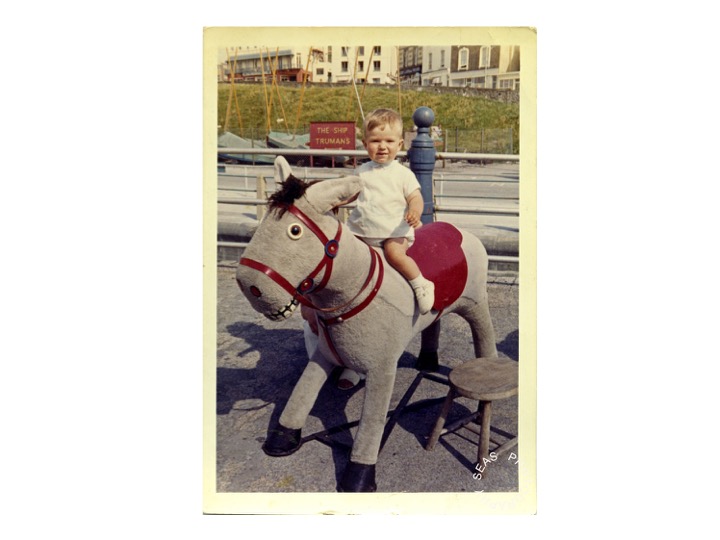

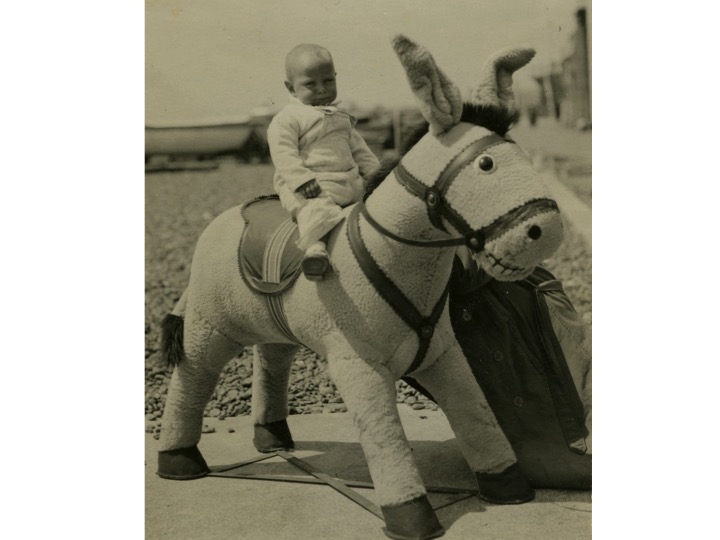

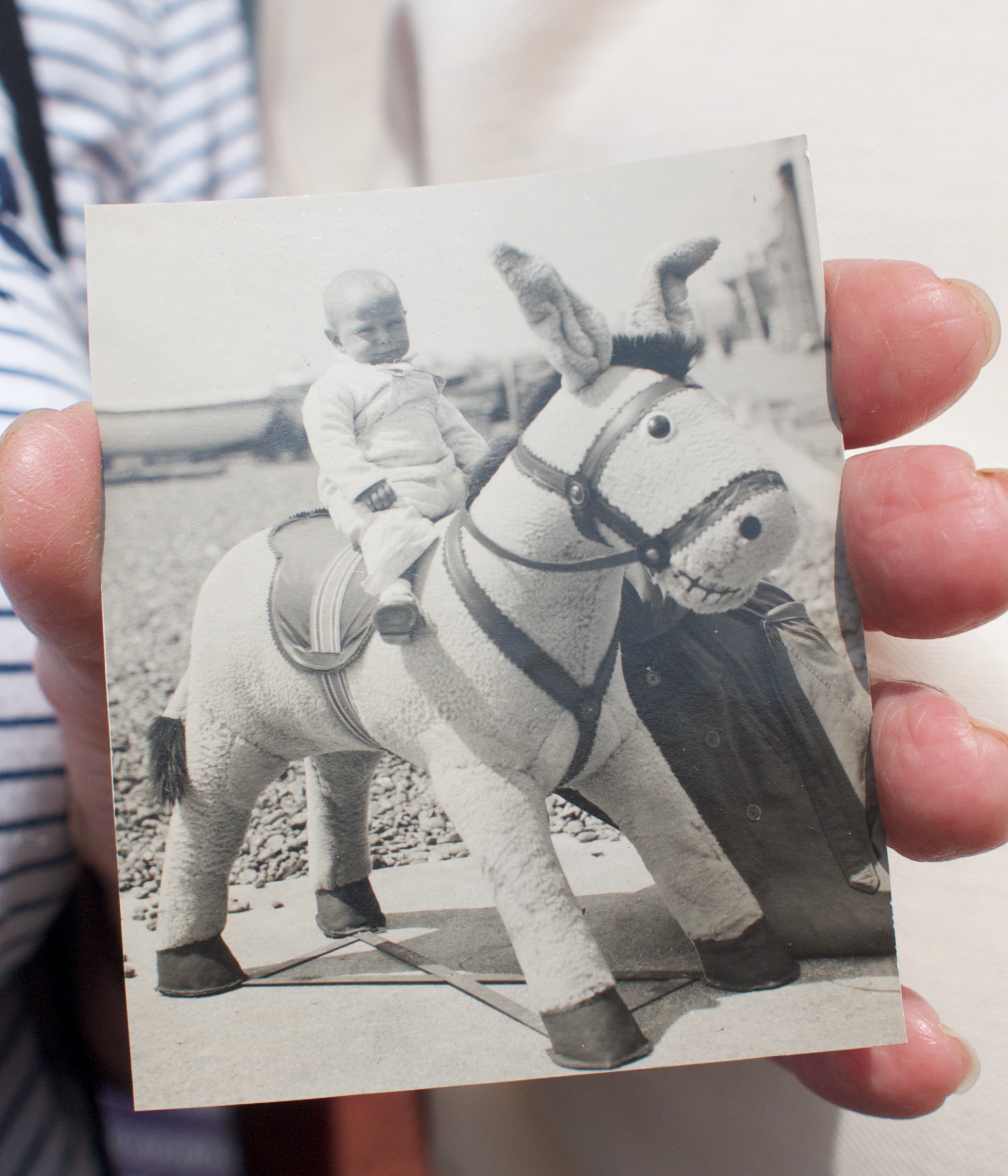

SLIDE

that of Mr and Mrs B, who travelled on a bus to one of our community collection days. They then patiently waited for over an hour to have a single image scanned – this image.

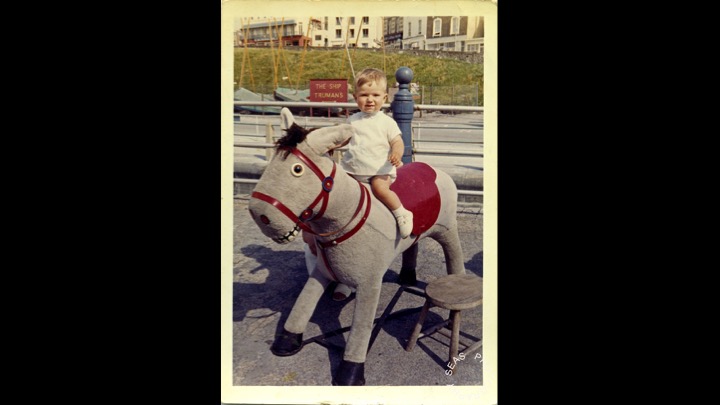

SLIDE

We have loads of these – commercially taken seaside photographs of small babies on ersatz donkeys.

But each one is someone’s baby; each one is the connective tissue between their now and their then – between the now and the (re)membered.

SLIDE

Mr and Mrs B’s baby died – this is one of the very few images that they have of her – they have only three photographs of their baby. The poignancy of the picture is of course amplified with this knowledge – their generosity in sharing this image and their memory of that specific day – the day, the moment that this photograph was taken is made all the more acute.

They told me this not as history – but as memory…

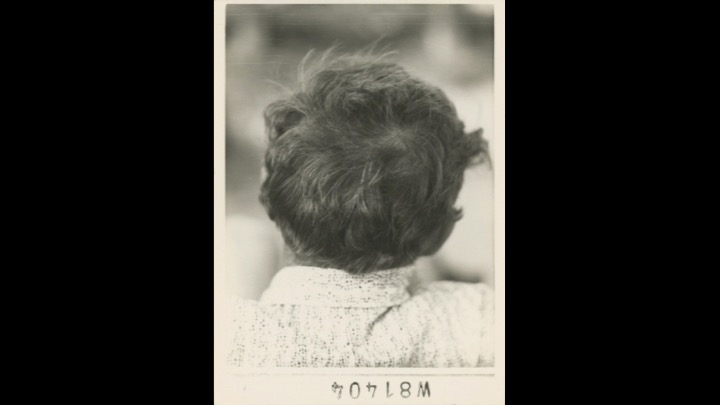

SLIDE

Of how that day had felt – a bright day, but still fresh enough to require them both to wear gabardine macs and for the baby to have hand-knitted layers on. Of how Mrs B had wanted the image to be ‘just of the baby’ and so had crouched down to the side, supporting the infant - at once she as mother, is present and yet concealed.

Mr and Mrs B’s spoken memory was a song well sung. And I took their narrative, as I scanned their image, as I touched the photograph of their baby daughter, I couldn’t help but feel emotionally moved and this emotion was heightened still further as I handed the photograph back to them – whereupon they in-turn touched it / stroked it – as if a relic.

This gesture of ‘touch’ I’ve subsequently seen over and over again at Community Collection Days.

Mr and Mrs B’s story was of course edited, their memories are edited / selective / re-membered versions of a past - in a similar way I too, in recounting their story here, edit / select and re-member.

Photography, as many have argued can be seen as provoking not genuine memory, but rather ‘counter-memory’. As Batchen asks: ‘has photography quietly replaced your memories with its own?’

Writing #2

As I noted earlier, I theoretically comprehend what I witness at Community Collection Days, but find the experience to be not only academically engaging but frequently emotionally touching too. And then… and then… a few months ago my Mother died.

Now, the peaceful death of an 80 year old woman cannot be defined as tragic, in the way that the death of Mr and Mrs B’s little child can be seen as such. But to loose one’s mother, regardless of how grown up we are, can inevitably bring deep sadness, mourning and in these relatively early days for me an emotion utterly akin to nostalgia in perhaps its original sense – a homesickness or longing – a longing for my mother’s corporal form. I quite literally miss her body.

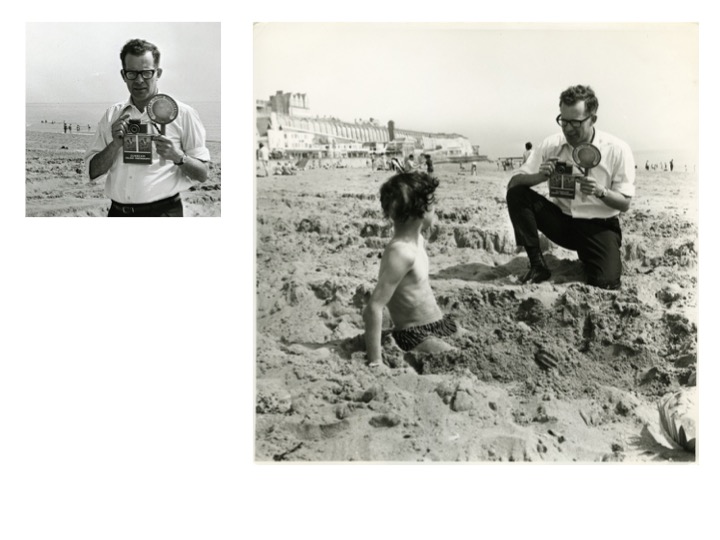

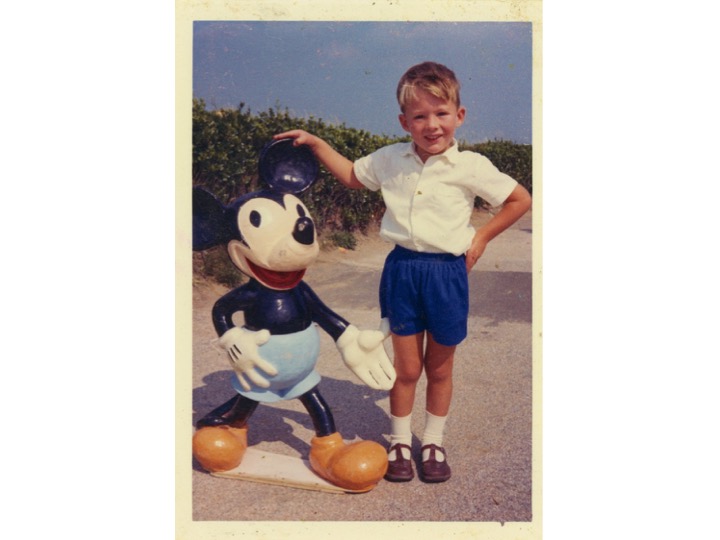

As a photographer, it is unsurprising that in this period of mourning I return repeatedly to family photographs, and here in one of her many boxes and carrier bags of pictures I found

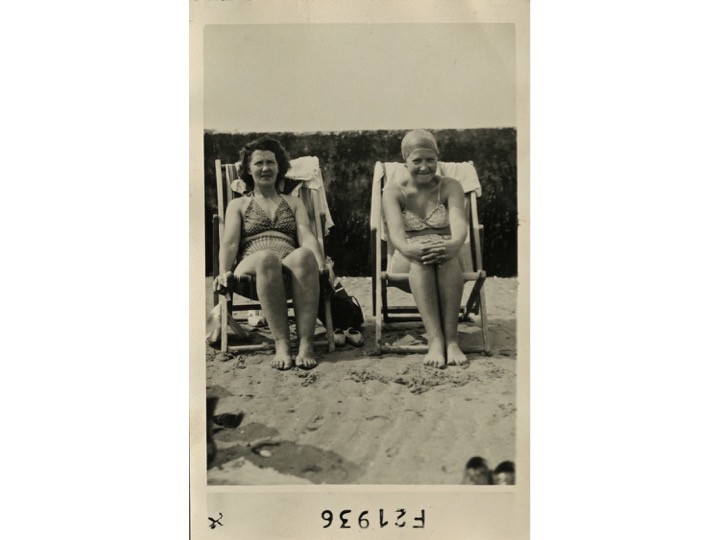

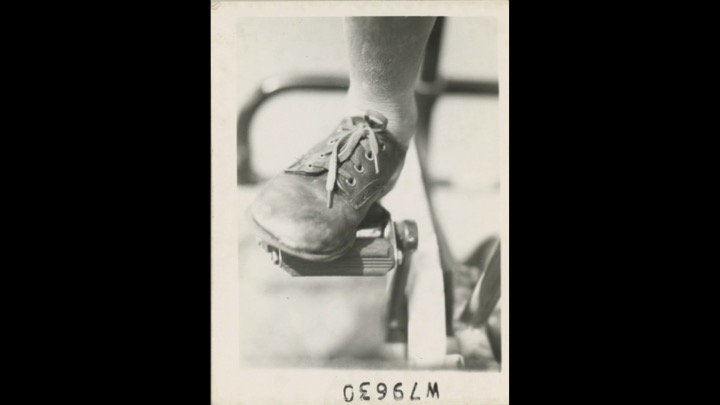

SLIDE

this 1950 commercial seaside photograph of my Mum, seen with her mother my Grandmother - at a time which is prior to my own existence. Here my Mother is just 14. I initially thought she was older, but the photograh was dated and through this unique commercial code – seen here – I can tell where it was taken – the small seaside town of Birchington which is close to where I still live and work.

As I held this unexceptional commercial seaside image, I became aware that like so many of the donors to the archive, that my fingers too were tracing my mother’s body, my own perhaps paradoxical maternal instincts wanting to be gentle with this diffident, gangly, awkward teenager.

I repeatedly came back to the out of focus shoes here in the bottom corner – are they hershoes..? I suspect so, but this makes me ache to an irrational level, as they appear to be such pragmatic footwear, she would have loathed them - she loved only pretty things. And her gesture – both facial and physical – floors me - I had seen her repeat this gesture only a month before her death when we attended a first and last meeting at our Hospice and her consultant tenderly told her, her life would be spent in a matter of weeks. She rocked forward, she clasped her knees, she smiled this exact same awkward smile - and thanked him.

Of course one can discuss this in Barthian terms… the very potency of Barthes’ writing both in Camera Lucida and the too often overlooked Mourning Diary is that at its core there seems to be something utterly universal... But as the Director of The South East Archive of Seaside Photography, in undertaking this work what has surprised me, and now touched me in a way I hadn’t previously envisaged, is how these humble, prosaic seaside postcard images provoke such forceful acts of re-membering and behaviours by the owners – by myself…

Such behaviors signify a value, an emotional connection, indicted by the tenderness in which the images are held, or the pride in which they are presented, or even in the way in which the donor might actually stroke the picture as relic. These commercially taken seaside photographs have a material potency – a material potency which arguably punches way above their weight and far supersedes both the picture’s actual monetary value and any original intentions on the part of the commercial seaside photographer.

Writing #3

The third written piece I want to share relates directly to more recent practice. To place this into context – this writing came from a coastal experience, which led to an image, which led to an internal wrestle as to what to do with that image. And I struggled for well over a year and concluded that the right – as right as this might ever be – the right way to articulate my experience was not wholly through the image, perhaps exhibiting the image within a show or submitting it for competition (certainly not that!) – rather it was through writing – through adding text to the image…

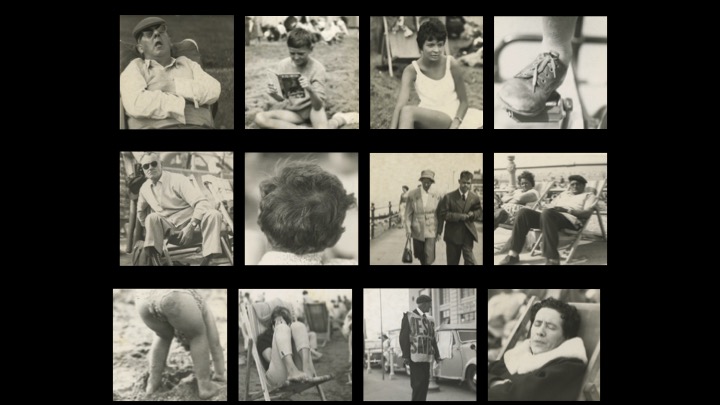

Much of the 2015 summer was spent walking the Thanet coastline with my camera. It sounds idyllic: waking, pulling on shorts and tee-shirt and straight onto the beach. ‘Idyllic’ is almost an accurate description. This part of my life has a beautiful simplicity – childlike rather than childish – playful, redolent of summers past. But in August 2015, the events shown in the image above served to reveal the denser undergrowth of photography.

However, research into seaside photography has taught me that being a beach-photographer – or a photographer who locates herself on the sands - has never been without difficulties. We naively think that this is the age of camera-suspicion, or more accurately, suspicion of the photographer’s motives. But history suggests otherwise.

Mid C19 seaside photographers plying their trade through cheap, while-you-wait photographic portraits were routinely characterised as ‘bodgers’ or ‘smudgers’, descriptive terms signifying a generalised ineptness and beyond this, a questioning of character.

In the late 1940s John Steinbeck makes reference to the continued suspicion prompted by the photographer and the camera’s presence:

The camera is one of the most frightening of modern weapons…the camera is a feared instrument, and a man with a camera is suspected and watched wherever he goes. (Steinbeck; [1949]1994:5)

While something of an exaggeration, the grain of truth is magnified in our contemporary era by further complexity: where suspicion is amplified through a general cultural anxiety around motivations for image making and image distribution and heightened further when children are included in the frame. The camera and thus the photographer in certain contexts can become, in Steinbeck’s assertion, ‘weaponised’; a threat amplified in contexts where states of undress are the norm and where children are at play.

Nevertheless, children are included in my image making. A continual delight for me, through my location at the seaside, is seeing ‘free range’ children, typically beyond the reach of structured parental-led activities. On the sands I observe, regardless of nationality, race or gender, children choreograph new friendships, share beach paraphernalia such as spades, buckets and simple fishing nets and how they play in parallel and together at the water’s edge. It is at this edge where I make my pictures.

But in the summer of 2015 something changed. In one moment I unselfconsciously raised my camera to make a picture and in the next a small, unnoticed child standing to one side pointed to me and cried out ‘Paedo!’. Within an instant a cluster of nearby children joined the chorus of “Paedo!, Paedo!”. In that moment, I realised that no public alarm was more piercing than that particular chant.

My camera came down and I flinched, at both the alarm call and the anticipated approach/reproach of the parents. I regretted too the cultural implications of such young children having this abbreviated word in their vocabulary. I was to learn over the course of the summer that this epithet is shared across many European languages. After that incident I developed what I can only define as a photographic stammer. I would head off each day, but return without even having lifted the camera. Or I would hesitate in bringing the camera up and so miss the picture.

The ripples of the chant were still there. But a timely visit to the Photographers’ Gallery and Shirley Baker’s exhibition ‘Women, Children and Loitering Men’ proved therapeutic. Baker used a TLR, and with good reason: the TLR camera unlike a rangefinder remains low, the photographer’s face remains visible and a conversation can continue whilst pictures are being made. I headed back out with my own ancient TLR and felt utterly liberated. Such a seemingly simple change meant that not only was I making pictures, but felt empathetically (re)connected to those I was photographing.

So it was on a hot dry day in August 2015 I found myself on Margate sands. I was in a light mood, carrying the TLR along with an unobtrusive digital compact and talking to people on the beach with my former ease. Suddenly a man collapsed and appeared to be in a very bad way. It quickly became apparent that things were critical. I sat, perhaps just twenty-feet away and along with many others watched how the young lifeguards with a doctor who happened to be on the sands and then the swiftly arriving paramedics worked tirelessly to save this man. His heart had stopped and the medical team kept going while his family of several generations gathered nearby in shattered, dignified silence.

During this time people stood and watched – I watched – and then to my left I saw a man, dressed for the beach, stroll into the scene and in a moment his long lens went up. I watched him for a while as he shot in rapid succession. Then, to his right, a group of young men whom I had earlier seen playing beach football clustered together, one of them pulled out a mobile ‘phone and took a group ‘selfie’, their pose carefully angled to allow the unfolding action to be in their pictured background.

Yet I too photographed this scene and later wondered about the doubly ironic notion of whether capturing an image of photographic voyeurism is also itself voyeuristic. To retreat from what I had seen, I wandered to my favourite coastal spot, far from the crowds of Margate’s main sands. I stayed there for a long time and as the sun set I saw a young father take his small child into the shallows for a final dip. The sun was now so low that they stood in the last beam of light. He was using his mobile ‘phone to photograph his child. He lovingly teased her to make her chuckle, their joyful chatter in a language unfamiliar to me. Almost involuntarily my camera came up and I took the scene. In many ways the image was of course clichéd, except for that moment reminding me of how the coastline’s edge photographically cuts both ways: from the misanthropic to the empathetic image. The most hostile act I had experienced on the beach had not been aimed at me; it was not the protective mother signalling that the camera was unwelcome, nor children taunting me with cries of ‘paedo’. Rather, it was witnessed by me, where the public death of a man became the focus of the photographic long lens and a seaside selfie.

I am a writer-of-sorts, who by and large uses the written word as much to present as to publish and regards photography-as-written as a powerful vehicle to talk about the things which matter to me – academically / culturally / aesthetically / emotionally. In doing so I am forced to reflect on my own photographic motivations and explore the continuing debates over what it is to be a photographer making pictures in public spaces, and

specifically, the seaside as location.

Thank you